For many decades there was a large wooden cross on the wall at the back of the St Johns Anglican Church in Lake St Cairns. Beside it, a framed paper explained that is was identical to the crosses used for the 350 (odd) members of the 51st Battalion (our local Battalion) who were killed in the liberation of Villers-Bretonneux in France. This one was dedicated to the memory of one of those young men and presented by his family. I don’t remember the name, but I remember the cross. I also remember how, when I was growing up, there were so many people still talked about, who had not come home from WW1, or come home badly scarred by their experiences, although WW2 was more recent. I resolved at quite a young age that I would go to the cemetery at Villers-Bretonneaux to honour those there.

I had a great uncle who fought on the Somme. He was an amazing guy. Many people in the district new Bob Trimble for his work in the Community – especially with the Cairns Show Association – but few knew he had a Military Medal for his efforts in WW1. King George V presented it to him, in person, on the Battlefield at the Somme, when he visited the frontline and met many of the soldiers.

So, when in December last year I was planning this trip, and found I could include an opportunity to do a tour of the Somme and Viller-Bretonneaux, I jumped at the chance. I “googled” for tours that I may be able to incorporate into my time frame and found “Chemins d’Histoire” who advertised tailor made tours for up to 7 people in a modern Mercedes van. I made contact and we were able to co-ordinate a date.

So here I was, in Amiens waiting to be picked up by the proprietor Olivier Dirson ,who had planned an itinerary that took in Villers-Bretonneux , La Boisselle, Pozieres, Thiepval, Beaumont-Hamel, and back to Amiens. The weather forecast had not been promising, but the day dawned clear but cold although it soon warmed up nicely. The drive through the farmlands was glorious, especially with all the spring flowers out. My school chum and travelling companion, Judy, was not particularly interested in the war history (as I am) but saw it as a wonderful opportunity to see the French Countryside, so had joined us for the day.

Our first stop was at the Australian National Memorial and Military Cemetery, which is on a small hill a few miles out of the town of Villers-Bretonneux . Like all the World War 1 Military Cemeteries I had visited before, it is beautifully maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. While we were there a man on a tractor was going back and forth slowly “aerating” the soil.

From this vantage point Olivier was able to explain how the battle progressed across the area. He was at pains to point out, both then and at several other locations, how most of the important infrastructure is still in the same place it was at the time of the conflict. The roads and railways, the towns, the streams, even some of the farm buildings, are all as they were then. So it makes it easy to follow where the battle progressed when all the same landmarks are still there. Also from the site on this slight rise you could see back as far as Amiens in one direction, “Villers-Bret” in another, and some of the other villages and towns around as well. It was a perfect place for him to explain it for us. I was impressed by not only his knowledge but his passion for it, and his wish for us to fully understand the feats that were achieved by the soldiers who fought this war, under the most trying of circumstances.

There were lots of workers in the area as the new Sir John Monash Centre is being built behind the current memorial. According to the sign on the fence “ the new centre and amenities respect the original Lutyens-designed memorial and cemetery and complete some aspects of the original design.” On the front of the site we could see where they were making the new car parking and “orientation pavilion” which will have visitor facilities (ie toilets) and provide info to guide visitors to both the Memorial and cemetery and the Sir John Monash Centre. On the other side will be new maintenance facilities. I thought it interesting that Olivier thought highly of Monash and thought it was a great thing that the Centre was being constructed, and in particular in the location they have chosen.

The Sir John Monash Centre (on course to open by Anzac day 2018) will tell the story of Australia’s experience in the Western Front in France and Belgium during the First World war. Over 295,000 Aussies served on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. 46,000 lost their lives and 132,000 were wounded. General Sir John Monash led the Australian Corp with outstanding success on the Western Front in 1918. He is best known for his 4th July 1918 victory at Le Hamel, which became a template for military operations that followed.

According to the brochure I picked up, the heart of the Centre will be a “deeply immersive experience unique to visitors centres in this are, delivering an educational (and emotional) experience in English, French and German. They will use leading edge technology, multimedia and objects significant to Aussies. The intention is that people will leave better understanding our roll on the Western Front but also the impact and the loss that was suffered by our young nation at that time”. If you are interest you can learn more for yourself at http://www.dva.gov.au/SJMC

We spent some time at the Memorial and cemetery, but declined to climb the Tower, (200 odd steps from memory) despite the fact the view would be outstanding. The view was pretty good as it was, on such a lovely day. I am always struck by the number of headstones with only “ A soldier of the Great War” and “Known unto God’, and those that have names were usually very young. Today I was also struck by the number of beautiful flowers that were part of the small garden that is in front of the headstones. It really is a beautiful place for a memorial and cemetery, and I mentally congratulated the people who had the forethought to choose this site.

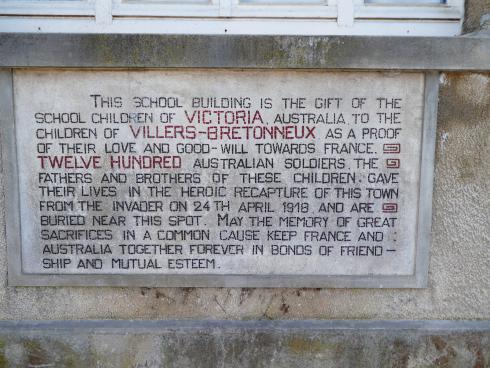

We then moved on to the nearby town of Villers-Bretonneux, and to their primary school – the Victorian School. I had heard so much about it and was pleased to be able to go there. There is a stone out the front that tells how it came about. Inside, I was surprised to see a sign hanging from the awning eves saying “Do not forget Australia” - bearing in mind it is now over a century, and the sign is freshly painted.

I guess we in Australia have no idea what it means to be conquered and then liberated in war, so we can never fully appreciate how, a century on, undertakings given are still being honoured. Visitors are allowed to use the toilets at the school but not when the children are there. I noticed there are wall paintings along what looked like the front of the tuckshop area, which seem to be of aboriginal designs – certainly in their style and colours. I meant to ask how they came about but forgot.

The Visitors Centre and Museum are having a major facelift and renovation, so we had to go in through the side door and around scaffolding. We did not mind. I could have spent the rest of the day – and probably half the next – at this museum. It was just lovely. The displays are relevant to their area and very lovingly done and maintained. Their appreciation for what the Aussies did shows everywhere. They have some items for sale – mostly books about the fighting in the area – but some memoirs and other things as well. I chose a small book of poems, written by soldiers serving in the Allied forces in that area as my special momento of that day. I know those who know my love of verse will understand that. I feel it is something I can use to contribute to the Anzac Day Commemorations at Watsonville in future years –besides, it will not take up much room in the port! I also contributed to their fund to maintain the museum as I think it deserves to be supported.

As we drove out of “Villers -Bret” Olivier pulled off to the side of the road. We got out and stood beside a ploughed field, so he could show us where the line of attack would have been. It was somehow surreal, standing in a freshly ploughed paddock, with the small of the freshly tilled soil still in the air, while he points to a line of trees in the middle distance and says it took them 11 days to move from there to the site behind us (on the other side of the road we had just pulled off) which is now occupied by a shopping centre and car-park. It really brings it home to you how tough the fighting was, when even I could probably easily walk that distance in an hour - two at most.

We then went probably only another kilometre and pulled into a side road and drove down to the small cemetery, sandwiched neatly between 2 major roads. The sign at front announces it is Crucifix Corner Cemetery 1917 – 1919. As we went in we noted that the graves to the left all had the same style of headstone as we had seen at the Villers-Bretennaux Memorial and Cemetery, but on the right it was different. Here there was a mixture of grey stone crosses and stone plinths with a carving on the top of them. Olivier explained these were the graves of French troops, the Christians with the crosses and the Muslims with the carved plinths. On seeing this Judy said, “The UK when it entered this war called on all their Colonies to supply troops to aid them, did France do the same?” Oliver answered that they had – which explained why there were so many Muslim graves alongside and mixed in with the Christian ones on the French side of the cemetery. It was something neither Judy nor I had ever thought about before, but made perfect sense once he said it.

I noted one that said “A British Officer (Lieutenant) of the Great War” and at the bottom “Known unto God”. In front and leaning against it was a small stone that said simply “Our Dear Son”. How they had identified this as being the grave of their son – still unnamed -I have no idea. Another had a name on it, of Private A Betteridge, and in front of that a piece of coloured Marble with “Never forgotten. Christine and Alan Betteridge”.

Our next stop was at the Lochnagar Crater Memorial at La Boisselle, which is now privately owned and free to the Public. It is where the British Armies 179th Tunnelling Company of the Royal Engineers tunnelled under a German strongpoint called “Schwaben Hohe” and set mines. It was exploded 2 minutes before 7.30am Zero Hour at the launch of the British attack on 1st July. It is the largest man made mine crater created on the Western Front in WW1. During the fighting over the next few days many bodies of both British and German troops fell or rolled into the crater. Some were retrieved but many are believed to be still there. There is now a group that is raising money and improving the safety and access to the site. They erected a cross from the beams of a church that was destroyed at Tyneside because that is where any of the soldiers came from originally. From here you can clearly see several villages/towns around the area, so you can understand why it was such an important position to hold during the war.

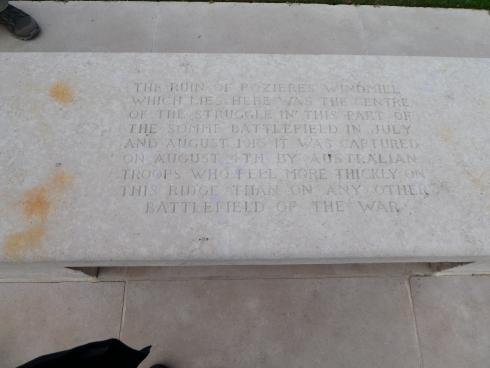

For lunch we went to a restaurant that was also a war museum. That was different and not like anything I had ever seen before. Still the food was fine and the toilets were clean and service was quick so we were soon on our way again. This time to what is known as the Windmill site – but there is no sign left of the windmill that once stood there, just a small rise in the ground. This is just outside Pozieres and after it fell on 23rd July it took until early August to capture the site of the towns windmill. Then until 5th September the Aussies were engaged in trying to take Mouqart Farm. In that seven weeks of this battle three Australian Divisions were engaged, they suffered 23,000 casualties of which over 7,000 died. War historian Charles Bean is quoted on the bench at the site “the ruins of the windmill marks a ridge more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth.”

The unknown soldier who sleeps peacefully at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, was brought home from this site. Some of the soil from this area was also taken home with him. At the ceremony when the coffin was laid in the Hall of Memory, Robert Comb, an AIF veteran of the Battle here, spread the soil over the coffin and is reported to have said “You are home now mate.”

The memorial is low key and has the flag of UK and France on either side of the stone that records that “More Australians fell here than in any other battlefield of the war.” An adjoining site has been recently purchased and it has small white crosses in the form of the Aussie Rising Sun Emblem from the hats. Olivier said he had been told they were going to try to get a more significant memorial of some sort erected there. Directly opposite – on the other side of the quite busy road is the Monument erected “to the memory of the Officers, Warrant Officers, non-commissioned Officers and men of the Tank Corp who fell during 2016 2017 2018. Above it says that near here tanks went in to action for the first time in the war on 15th Sept 2016. All around is peaceful farming land and countryside with one of the small cemeteries that dot the countryside in this area in clear view.

When I told a friend of mine, Eva Rawlins of Gordonvale that I was going to do a tour of the Somme battlefield she said “My Dad is buried over there. He never saw me and I have never seen his grave. Do you think you could take a photo for me?” Eva was 100 at the time. Now I ask you – how could you refuse a request like that? I said if she got the details of where he was buried I would try to do that. She had the info back to me within a few days. So our next stop was a detour from the original itinerary – to Bulls Road Cemetery which is just outside the village of Flers, to find the grave of Private Frederick John Griffin – formerly of Gordonvale North Queensland. Earlier when we had been in “Villers-Bret” I had gone to a florist to buy a wreath or some flowers to lay, but once I got there I decided to buy a pot with living plants in it, so I could leave something that would hopefully be more permanent. I found a lovely pot with a Peace Lily and a couple of other plants and thought that would be just the ticket.

We found his grave easily, it is in the front row as you come in the entry. I took a photo of it. Then I put the pot beside it. I noted that there were not as many flowers near his grave as there usually are in these places, so was doubly pleased I had chosen as I had. I watered them well, with water I had brought for that purpose, and then took a photo of the grave with the pot in place. Every one of these cemeteries has a metal depository in one of the entry pillars. It contains both a Register of those who are buried in this cemetery, and a Visitors book. I signed the Visitors book as having been there as a representative of his daughter who was about to turn 101 (her birthday was 5 days after my visit to Bull Road) and took a photo of the entry for her Dad in the Register. I also took several photo’s of the cemetery and the surrounding area. They are doing some renovations to one end of the boundary so it was a bit untidy, but otherwise it is like all the others, beautifully kept and in a wonderfully peaceful countryside setting. (I might add here I then sat up till midnight, battling with on again/off again free wifif, to email the photo’s home to Eva’s daughter so she could see them asap.) I felt very privileged to be able to do this for her.

We could see our last destination for miles before we reached it. The British Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme stands on a high ridge and towers above everything for miles. It dominates the skyline around it. It is quite a complex design that is 43 m high, above the level of its podium, which to the west is 6.1 m above the level of the adjoining cemetery. The foundations are 5.8 m thick, because of extensive wartime tunnelling beneath the structure. It has the names of around 72,000 British soldiers who have no known burial site. (As one of them is identified as having a burial site his name is removed from the wall.) There are many noticeable ‘spaces’ as more and more are identified using new technology. Amongst the names are 7 VC winners, and I noted that when any have won a medal it is noted beside his name. Also commemorated are five First Class English/Irish Cricketers, 7 Rugby Internationals (English, Scots, Welsh) 1 Welsh Soccer International, Composer George Braithwaite and Irish economist, poet and former British MP Thomas Michael Kettle.

Inside the Memorial are 16 stone laurel wreaths, which are inscribed with the names of the sub-battles – including Thiepval Ridge.

The adjoining cemetery has 300 French (253 unknown) and 300 British (239 unknown) graves. The unknown graves of the British bear the usual “known unto God” – the French grey stone crosses of the unknown graves have the word “inconnu” (unknown). The Cemetery Cross of Sacrifice usually just bears the words “Lest we Forget” but the one here bears an inscription “That the world may remember the common sacrifice of two and a half million dead, here have been laid side by side Soldiers of France and the British Empire in eternal comradeship.”

(In case you are wondering why the number of unknown bodies is so very high for this war, I was told by a historian years ago that it has many reasons – some to do with the heat of the battle, the lack of time (or sometimes manpower) to bury them - but the biggest reason is that their ‘dog tags’ were made of a strong form of cardboard, which did not last long in the mud that was the constant companion to all the fighting. Sometimes a grave will mention the regiment they were a member of, as enough of the uniform remained intact to at least see that much, but often the clothing too was not recognisable. Once metal ‘dog tags’ were introduced, the problem to a large extent solved itself.)

Around the memorial and in the adjoining stands of trees there were lots of wildflowers celebrating spring. From here I could also see at least two other small cemeteries in the farmlands. It was a peaceful place – as they all are.

In 2004 they built a Visitors centre, but it is down the hill and out of sight of the Memorial - which I thought was a great idea. Mind you inside the visitors centre they have a scale model of it, and I have to question why one would need a very large, scale model when the real thing is 5 minutes walk up the hill.

From there we had a pleasant drive through the French countryside back to Amiens. Olivier and Judy chatted on the journey, but I found I was locked in my own thoughts and trying to take in all I had seen, heard and experienced that day. I felt very close to my Uncle Bob. I think I fully understood then, a comment he once made to me (as we sat in the shade of my mango tree and pulled weeds.) I had asked him why he seldom talked about his time in the army and when he did he always told ‘funny’ and amusing stories. I have never forgotten – he said “If I told them what it was really like, no-one would believe me.” I guess he was right.

It was a very emotional day for me as I said, but it is something I am so glad I did and I will remember it for the rest of my life. I am also so grateful to Olivier Dirson from Chemins D’Historie Battlefield Tours. When he said he would personalise the tour for me, he kept his word. All the places we went to were battles that my Uncle Bob was involved in. I had sent him Uncle Bob’s war details, he did the research and planned the itinerary accordingly. I think that made it so much more relevant to me. I highly recommend him to anyone who wants a personalised tour. His website is http://cheminsdhistoire.com and you can email him direct at contact@cheminsdhistoire.com . Of course having a warm (for that time of year) day with lots of sunshine, always helps make your day, especially when you are driving around the countryside that is blooming with spring flowers.

FOOTNOTE.

In The Irish Times on Monday April 10th when in Sligo, I noticed an item on the front page written by Ronan McGeevey, with the headline “Grave of Irish man killed during the first World War finally identified”. I quote it here verbatim.

“Like so many parents John and Jane MacHutchison endured the double agony of not only losing a son in the first World War, but also having no place to mourn his passing.

Lieut William Frederick MacHutchison from Darty Road in Dublin disappeared during fierce fighting in March 1918. He went off in the direction of a captured German village in France to get treatment for a bullet wound to his head and was never seen by his own side again.

Until now, MacHutchison was one of 526,816 British soldiers who died n the war and have no known grave. He was one of the “Pals at Gallipoli” the middle-class Dublin boys who signed up en-masse to fight in the war. Three years after he died, his family placed an in memoriam notice in The Irish Times stating he was ‘missing, believed killed” in France.

Ceremony.

On Wednesday MacHutchison will no longer be among the missing. His grave has been identified and a rededication ceremony will take place at Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery in the Somme region of northern Franc. Among those who will attend the ceremony will be MacHutchison’s grand-niece Sandra Harper from Belfast and her son Colin. Mrs Harper’s Grandfather John was MacHutchison’s brother.

Ms Harper said news her great uncle’s grave had been identified after 99 years left her “gobsmacked”.

“I feel very sad that his parents and his brothers and sister did not know that he had a proper grave,” she said.

She has determined that the inscription will read “Lovingly remembered by his parents John and Jane, brothers George and John and sister Kathleen.””

On the TV that night I saw someone being interviewed (didn’t catch a name) who said it was important to the families, who still have missing family members from that war that the search continues to identify bodies, and give some sort of closure. He said that is was surprising how many of them are still grieved for – even though the family members who knew him were no longer alive.

I found it quite poignant – having so recently been there and seen for myself the acres of gravestones with the inscription “Known unto God” – or similar. As I had not yet got around to finishing my blog for my tour of the Somme, including a visit to the Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery where the ceremony was to take place, I have taken the opportunity to include it as a footnote.